This page is a preflective course dossier for PSC 101: Intro to American Politics. It details how I plan to teach the course and the types of activities I plan to use to encourage engaged learning among my students in a face-to-face setting. This course is intended to be taught at the University of Alabama, but it could be adapted to other institutions or even online environments. The expected class size is between 30 and 40 students with most of them being underclassmen.

My Teaching Philosophy:

Students can best learn political science by experiencing how the abstract concepts taught in the classroom play out in the real world of politics. My goal when teaching a course is to get students to understand how the content they are learning can and should affect the decisions they make as administrators, campaign managers, and candidates/elected officials in their own right. While I understand that many students enter political science to pursue law, my own specialization focuses on the political and governing processes of the United States; therefore, my goal is for students to understand the arena of politics and the arena of law is best left to scholars in that field.

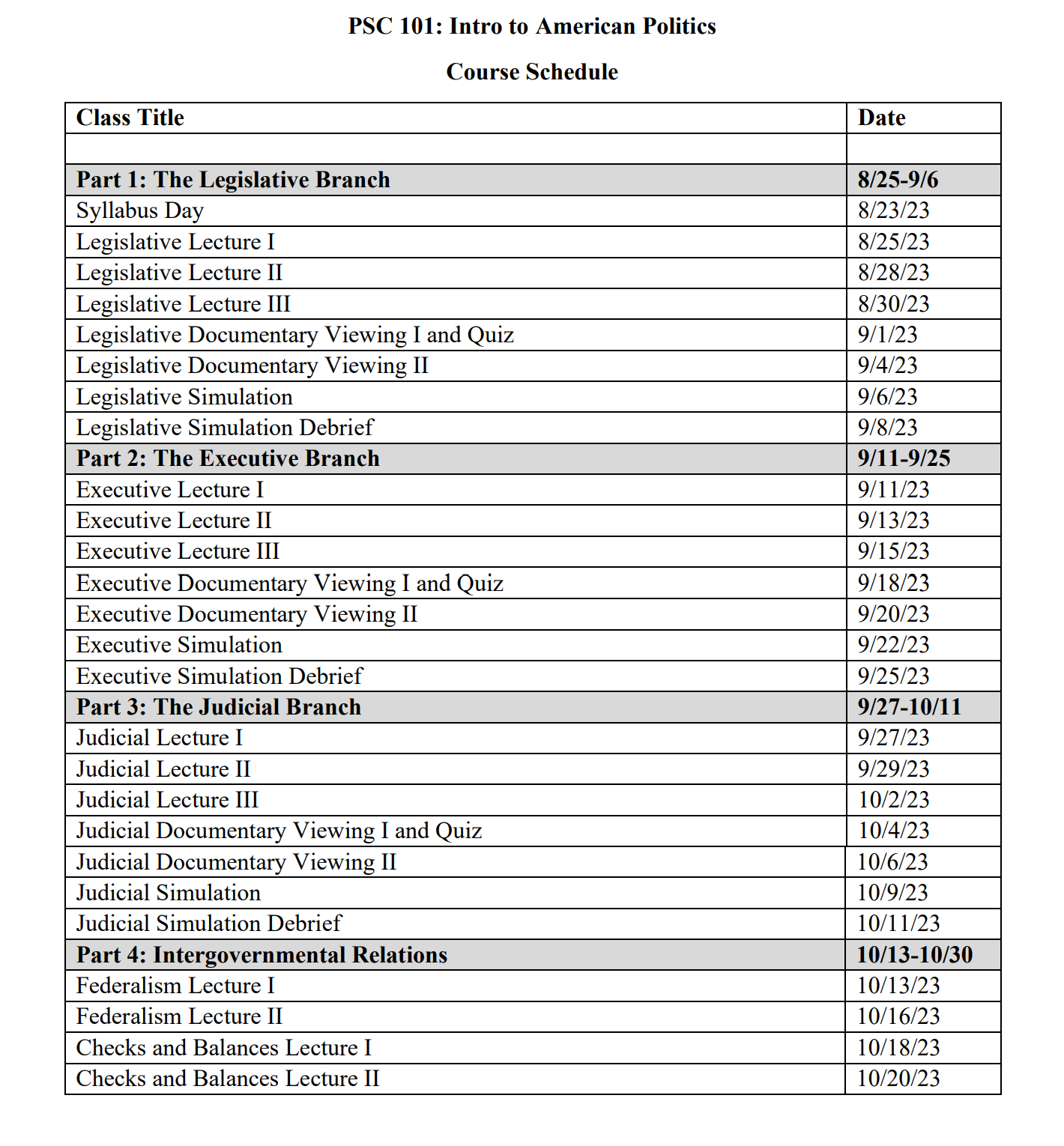

I believe that students learn through a process of repeated exposure and application of material. My own learning experiences were colored by my time as a student-athlete, and I find that it is better to coach students than to just talk at them. Most, if not all, of the courses I teach will feature a simulation or application component. For example, in my proposed design for PSC 101: Intro to American Politics, I have each unit on the three branches of government capped by two activities: a historical analysis and a simulation. The historical analysis component has students apply the concepts of the course to real life situation by watching a documentary and writing a response paper that discusses how the concepts they learned in the lecture and readings were carried out by the political actors in the real situation. The simulation component places the students in the roles of those political actors and enables them to apply the concepts to make decisions in response to a fictional crisis. An upper-level course would feature a greater number of these activities in order to allow students to incorporate feedback. For example, I would design a course on The American Presidency in the manner of a flipped classroom: students would watch a 20-30 minute lecture online, do a reading, and the in-class portion would be a walkthrough of a case study in presidential history. The walkthroughs would give students opportunities to think ahead on what decisions should be made given the context and then to see how the decision the President made plays out.

Assessing students’ learning is best done by giving them room to offer interpretations. While traditional exams and quizzes certainly have a place, especially in ensuring that students read, I find that many of the concepts of political science lend themselves better to open-ended questions in short answer or essay formats. Students come to college classrooms from many diverse backgrounds, and those backgrounds should produce variations in the ways they consider the political process. While we do not ask normative questions in political science, our biases towards the way we think things ought to be are impossible to truly remove from the traditional lecture and exam format. By providing students with the opportunities to articulate their own thoughts on how political science concepts play out, we give a microphone to viewpoints that are under-represented in academia and encourage students to demonstrate their knowledge combined with their own experiences.

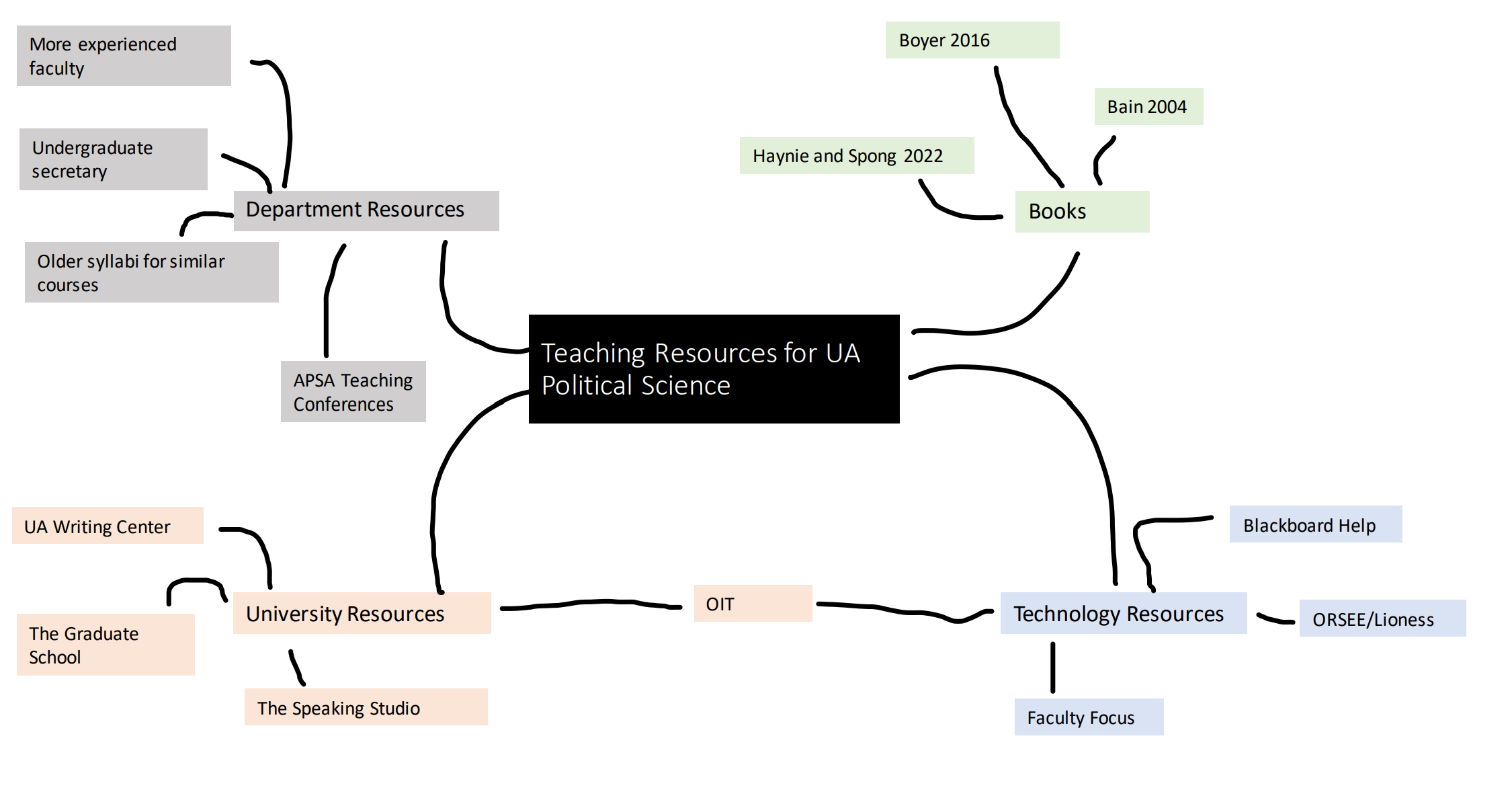

Pictured below is a personal learning environment (PLE) map that displays the resources available to political science instructors at UA.

General Course Flow

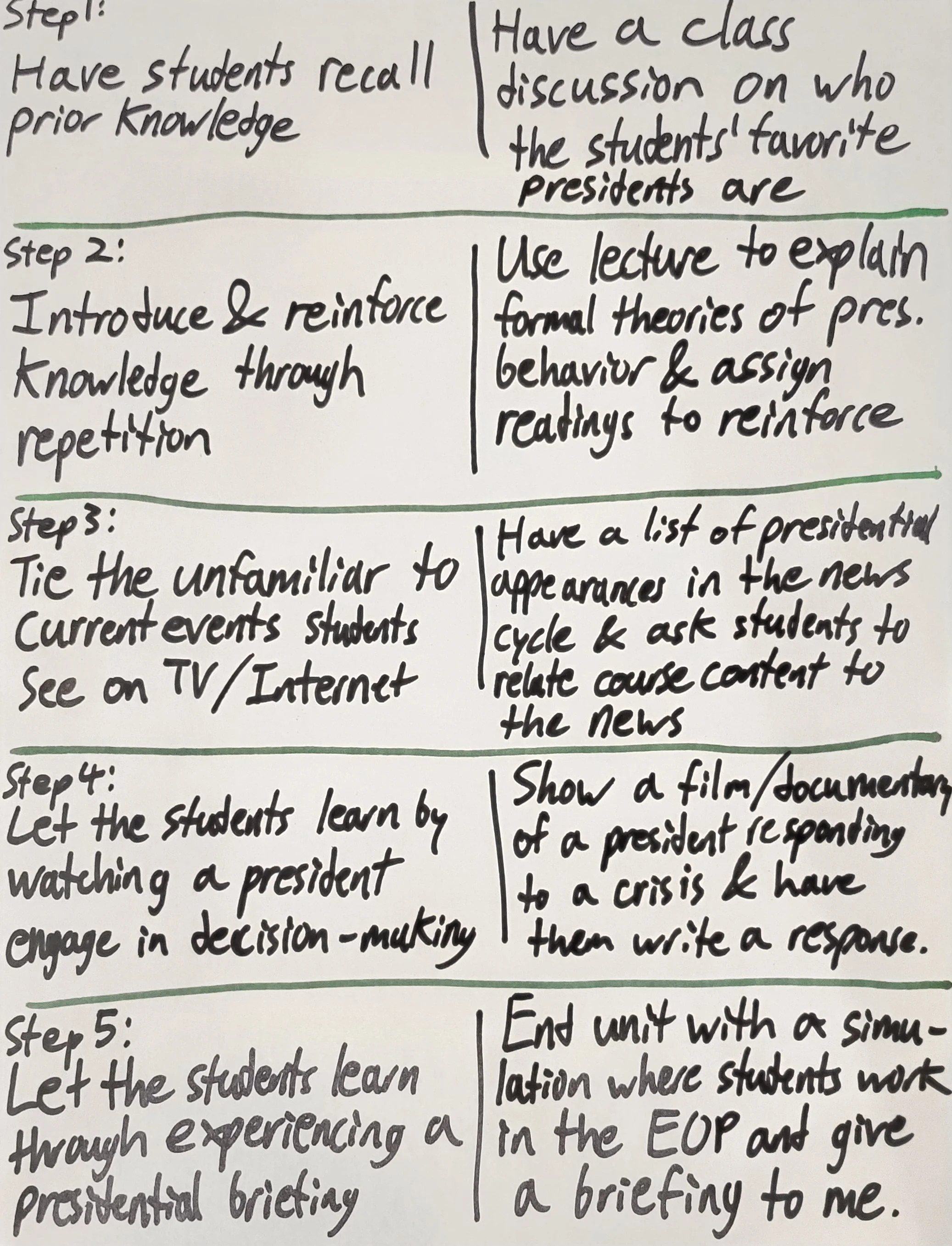

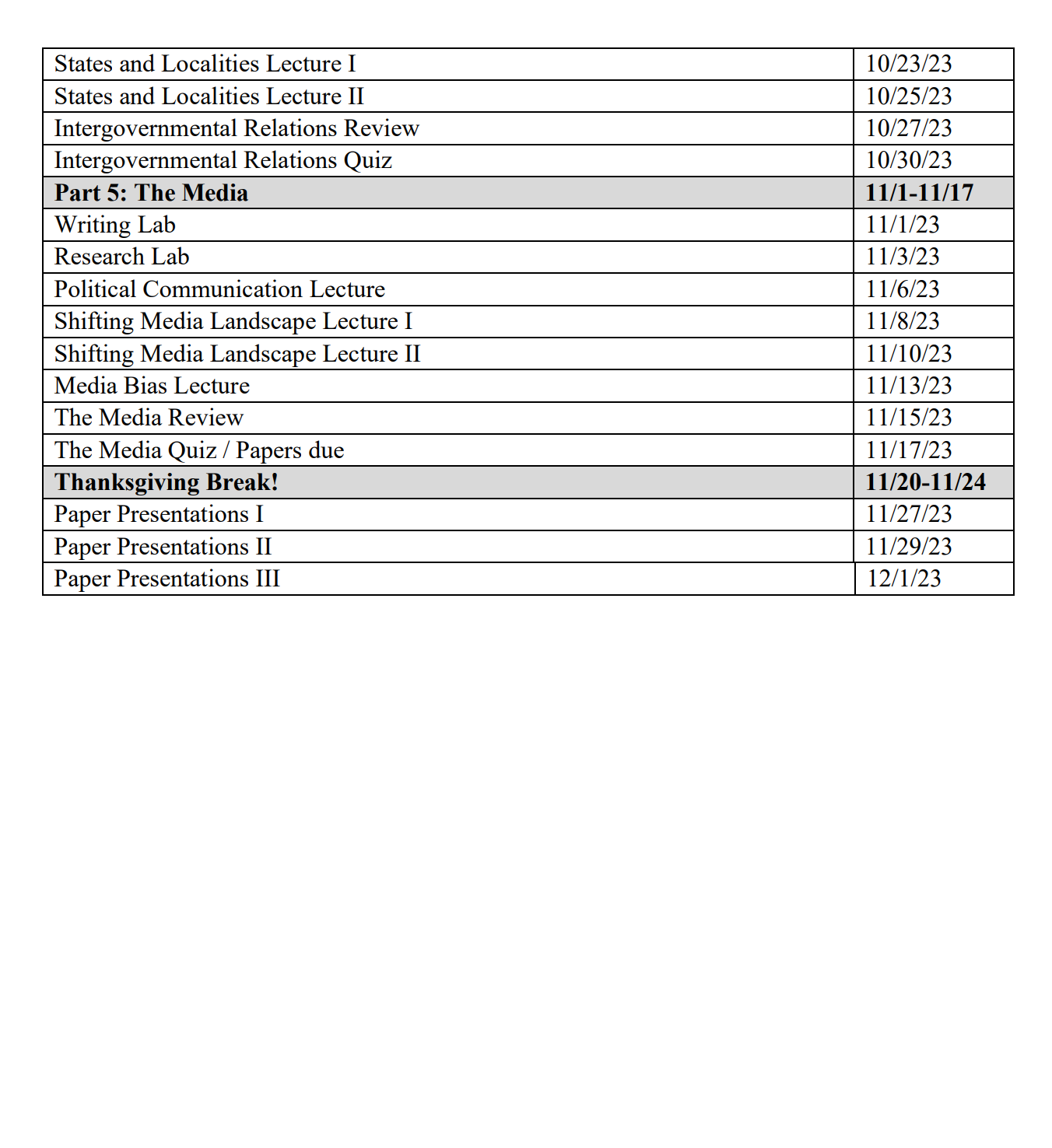

The graphic organizer to the right demonstrates the flow of each of the major three units of the course: legislative, executive, and judiciary. This chart uses the executive branch as the example. Each unit will includes periods of recall and lecture, then follow those with classes focused on observing the course content in context (both current and historic). Each unit is capped by a simulation exercise instead of an exam. This provides students with the opportunity to apply their learning to real world situations.

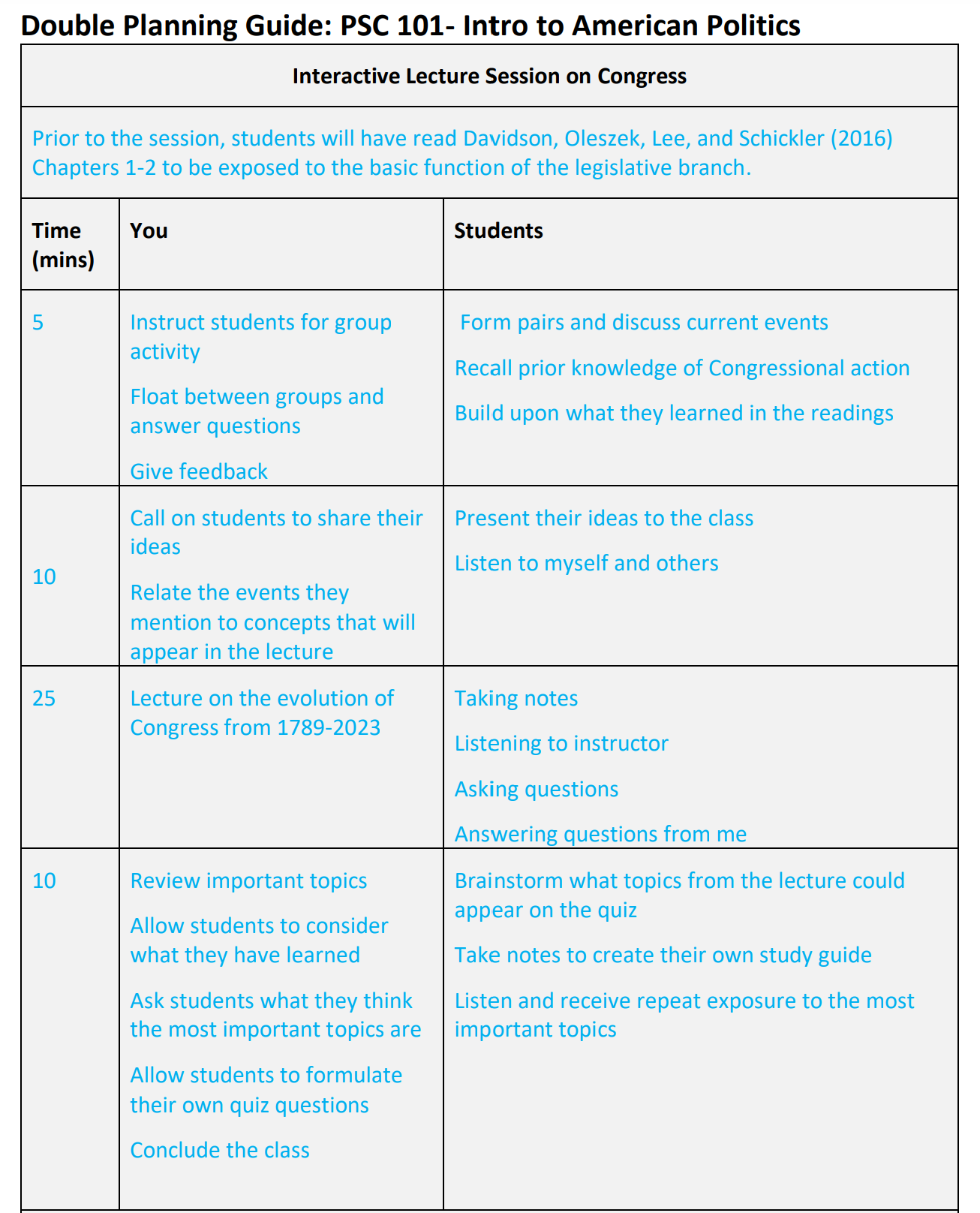

Students will have a quiz to cover the content from lecture and readings for each unit. Giving a quiz instead of an exam takes the pressure off of students while still requiring them to study and become familiar with the course content. Here is a link to an example Kahoot that will be used in preparation for the quiz on the Legislative unit in PSC 101.

The discussion questions provided to the right represent various types of questions that are intended to guide a discussion of the American presidency in the Executive unit.

While discussion is generally difficult to create successfully among a group of large students, these questions can be adapted as prompts for small group activities such as Think-Pair-Share that encourage students to learn together and build relationships.

What role does the president play in the public policy cycle?

This exploratory question asks students to identify the role of the president in creating and implementing policy, which tests their knowledge of the Constitutional limits of the office and the norms of Congressional lawmaking.

How can we account for presidents engaging in policy pandering when their popularity is low but not when the economy is underperforming?

This challenges the students to develop a theory behind empirical observations of presidential behavior based on the findings of Canes-Wrone and Shotts (2004).

How does the modern presidency (FDR to Biden) compare to the presidency in the earlier years of the republic?

This relational question asks students to compare and contrast modern and pre-modern presidents. It also leaves great room for an 'it depends' answer, as Skowrownek (1993) argues that modern and pre-modern presidents degree of comparability depends on the level of crisis they faced in office.

Why did Presidents Obama and Trump both pursue their main legislative accomplishments (the Affordable Care Act of 2010 and the Tax Reform Bill of 2017) in their first two years in office?

This diagnostic question invites students to explore the impact of the election cycle on presidential policymaking and the degree to which presidents are motivated by external factors.

When faced with the Covid pandemic, how should President Trump have reacted?

This action question allows students to apply their knowledge of the presidency (both institutional and public-facing) to prescribe new and/or defend the actions of the Trump Administration in 2020. While potentially controversial, the rules for productive discussion that the class creates on syllabus day should allow there to be a productive discussion on how Trump could have better produced a rally-around-the-flag effect or if that effect was even possible.

If a major volcanic eruption were to occur in Yellowstone, what should the president do in response?

This cause and effect question provides an opportunity for students to explore how the president can use the bully pulpit to lead the public, mobilize the executive branch bureaucracy to respond quickly to natural disasters, and ask Congress for legislation.

What are additional ways that presidents can use the veto power beyond simply rejecting legislation?

This extension question asks students to think outside of the box and consider how the threat of the veto can alter legislation that comes to the president's desk and how symbolic vetoes can change the way the president is perceived, despite Congress having the ability to override.

Suppose President Obama had nominated his least opposed Republican for the Supreme Court in 2016 rather than Merrick Garland, would this nominee have received a vote? Why or why not?

This hypothetical question gives students a chance to explore presidential-senatorial confrontations and examine the multifaceted motivations of the Senate when it refuses to act on presidential requests.

Based on your textbook readings, what is the most important power the president has at their disposal?

This gives students an opportunity to debate over the various tools presidents can use, such as the veto, nominations, executive order, proclamations, and the unofficial tools like going public.

What is the theme of empirical studies of presidents' attempts to change public opinion?

This summary question gives students many angles from which they can discuss presidential persuasion, such as the 'teaching' of Neustadt's presidents or the hopelessness described by later scholars such as Edwards.

What if you were a White House staffer briefing the president on potential nominees for a recently vacant Supreme Court seat?

I love this problem question because it is the basis of an entire simulation activity that I use as a project in the class.

From whose perspective would President Wilson's tour of the US in support of the fledgling League of Nations made the most sense?

This interpretation question gives students an opportunity to relate the Neustadtian perspective of the president to a historical event. Woodrow Wilson's ill-fated tour of the country also crucially leaves the success of the endeavor up to debate, as Wilson suffers a stroke before the task is complete.

Knowing that President Ford's pardon of Richard Nixon prevented unrest across the country post-Watergate but also sank Ford's approval rating for his entire time in office, how should President Biden respond to the indictment of Donald Trump?

This application question takes the one case of a former president facing prosecution and applies it to the current goings-on in New York. As with the Covid question above, guidelines for civil discussion are heavily leaned upon when tackling current events that have a partisan skew.

Are executive orders or pieces of legislation the most effective route for presidents to pursue their policy agendas?

This evaluative question asks students to make a judgment on whether they value the quick response of the executive or the solution permanence of the legislative more. While drawing attention to a fundamental distinction between the two branches, this question can also open students up to a new perspective on executive orders in general.

How might we best apply the scientific method to the study of the presidency?

This critical question asks students to examine the potential benefits and pitfalls of applying research methods to presidential studies. This is a notoriously difficult application due to the small number of presidents available for study and the lack of comparable situations between them. This question is intended for students to simply grasp the difficulties of creating generalizable theories of the presidency.

This concludes my preflective course dossier for PSC 101: Intro to American Politics. No syllabus is provided because the department encourages GTA instructors to use the same syllabus when teaching their first classes. Crafting this dossier over the course of the Spring 2023 semester has given me many teaching strategies to think about when I am designing my own courses, and my experiences here may even allow me to design my own syllabus in the first semester.